Infection prevention

Resource

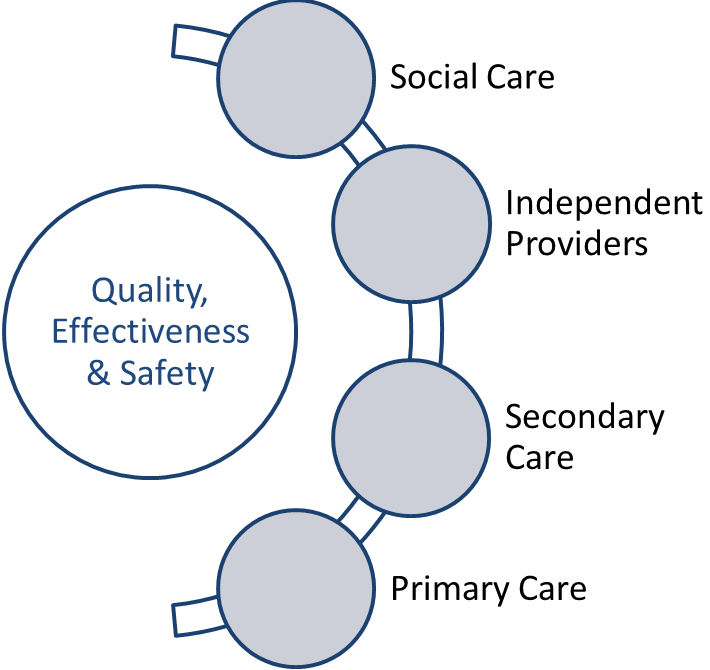

West Hampshire Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) employs a Specialist Nurse in Infection Prevention. The core responsibility of the Specialist Nurse is to work with providers across the whole health economy to prevent, reduce or control infection and to provide assurance to the CCG that registered providers are compliant with the Health and Social Care Act 2008 and Code of practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance (2010).

Under the Health and Social Care Act, registered providers of healthcare must, so far as reasonably practicable, ensure that; service users; persons employed for the purpose of the carrying on of the regulated activity; and others who may be at risk of exposure to a health care associated infection arising from the carrying on of the regulated activity, are protected against identifiable risks of acquiring such an infection.

Good infection prevention and control is essential to ensuring that the local population receives safe and effective care, wherever the Clinical Commissioning Group commissions. This report clearly articulates the work of the Infection Prevention Specialist Nurse in reducing, controlling and preventing infections. It provides details of the CCG’s work over the last year, and how our specialist nurse has influenced local, regional and national practice.

Reducing and preventing infections remains a high priority for the CCG and the report identifies those work streams will continue into 2018/19 to further support safe and effective care for our local population.

Read what the CCG has been doing in 2017-18 to help reduce and control infection:

Antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats facing us today.

Without effective antibiotics many routine treatments will become increasingly dangerous. Setting broken bones, basic operations, even chemotherapy all rely on access to antibiotics that work.

To slow resistance we need to cut the use of unnecessary antibiotics. We’re asking everyone in the UK, the public and the medical community to become Antibiotic Guardians.

Choose one simple pledge about how you’ll make better use of antibiotics and help save this vital medicine from becoming obsolete.

www.antibioticguardian.com/

Download the complete Community Management of CDI Algorithm for printing: Community CDI Algorithm (DPC Approved).pdf [pdf] 324KB

Abbreviations

BD – Twice daily, BP – Blood Pressure, CDI – Clostridium difficile Infection, CCM – Consultant Medical Microbiologist:

- CRP – C-Reactive Protein,

- FBC – Full Blood Count,

- FMT – Faecal Microbiota Transplant,

- H2RA – H2 Receptor Antagonist,

- QD – Once daily,

- PPI – Proton Pump Inhibitor,

- QDS – Four times daily,

- TDS – Three times daily,

- TPR Temperature, Pulse, Respiration,

- U&E – Urea and Creatinine,

- WCC – White Cell Count (total)

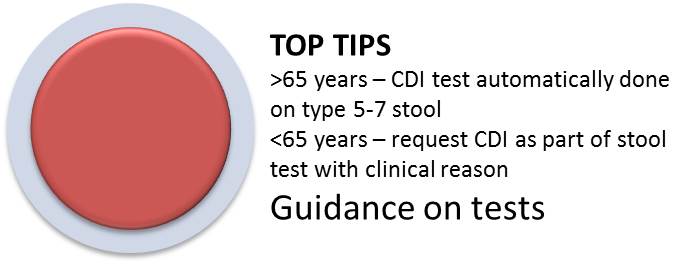

Disease Classification

Clostridium difficile causes a spectrum of disease, ranging from asymptomatic carriage to severe and life threatening illness. CDI can also lead to life-threatening complications such as severe swelling of the bowel from a build-up of gas (toxic megacolon).

Symptoms of Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) can include:

- diarrhoea (types 5-7 Bristol Stool Chart)

- temperature above 38ºC (100.4ºF)

- painful abdominal cramps.

- CDI should be considered in patients presenting with diarrhoea with no other obvious cause (e.g. history suspicious of food poisoning, viral gastroenteritis or foreign travel), particularly in the presence of the following risk factors:

Asymptomatic carriage is seen in up to 3% of healthy adults, but may be as high as 20% in elderly patients in hospital1 and 50% in some long-term care facilities2. Over 80% of reported cases occur in people aged over 65 years2 It most commonly affects people who have been treated with antibiotics.

Spores of the Clostridium difficile bacteria can be passed out of the human body in faeces (stools) and can survive for many months, and sometimes years, on objects and surfaces. Latest evidence also suggests that symptomatic patients can also carry high levels of Clostridium difficile spores on the skin, making hand washing with soap and water (not alcohol gels) essential.

Prevention of CDI in the community

Probiotics: There is currently conflicting evidence for the use of active culture yoghurts / probiotics to restore intestinal bacterial diversity but probiotics containing Saccharomyces boulardi or Lactobacillus species may help to prevent CDI relapse and could be worth pursuing in some patients.3 Care should be taken when administering live probiotics to those with severe immunocompromise. Patients should be advised to purchase probiotic products themselves.

PPIGastric acid suppression: Gastric acid suppressing medications are shown to increase the risk of developing CDI and may contribute to re-infection. There is a clear dose response effect between the degree and type of acid suppression and CDI4-7:

No gastric acid suppression odds ratio (OR) 1

OR 1.53 (95% CI, 1.12-2.10) H2 Receptor Antagonist

OR 1.74 (95% CI, 1.39-2.18) daily PPI

OR 2.36 (95% CI, 1.79-3.11) more frequent PPI.

Reviewing the need for acid suppression and where possible stopping PPI’s (using a tapering regime with concomitant alginate cover for patients who have been receiving PPI’s for more than eight weeks) or switching to a H2 Receptor Antagonist or lower risk alternative is likely to be beneficial.

Antimicrobials: All non-CDI related antimicrobial treatment should be stopped in patients with CDI wherever possible. Exposure to any antimicrobial agent generally increases the risk of CDI and stopping concurrent antimicrobials may give intestinal bacterial flora the opportunity to repopulate4-8.

No antimicrobial therapy odds ratio (OR) 1Antimicrobial risk

All Antimicrobials OR 6.91 (95% CI 4.17-11.44)12,13

In community-associated cases, the following antimicrobials carry increased likelihood of CDI:

Clindamycin OR 16.80 (95% CI 7.48-37.76)8,12

Cephalosporins OR 5.68 (95% CI 2.12-15.23)8,12

Quinolones OR 5.50 (95% CI 4.26-7.11)8,12

Penicillins OR 2.71 (95% CI 1.75-4.21)8,12

Macrolides OR 2.65 (95% CI 1.92-2.43)8,12

Trimethoprim & Sulfonamides OR 1.81 (95% CI 1.34-2.43)8,12

Tetracyclines – no significant association seen

Diclofenac: has been linked with an increased risk of CDI. Where possible, consider stopping.9

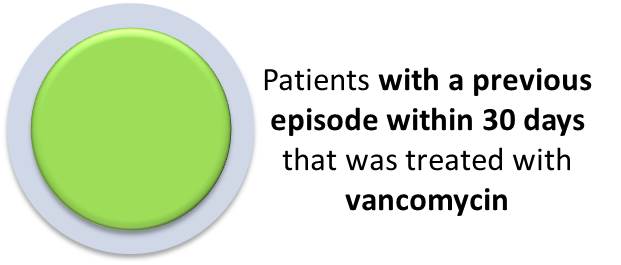

Relapse therapy:

Tapering vancomycin: Where the patient has already been treated with and failed to response to oral metronidazole or relapsed, use oral vancomycin 125mg QDS for 10-14 days. The use of tapering dose vancomycin may also be helpful10:

· Week 1: 125mg QDS

· Week 2: 125mg TDS

· Week 3: 125mg BD

· Week 4: 125mg OD

· Week 5: 125mg alternate days

· Week 6: 125mg every third day

Fidaxomicin: is a relatively new macrocylic antibiotic licenced for the treatment of moderate to severe CDI and has been shown to be non-inferior to vancomycin.10,11 There is evidence that it reduces the numbers of patients who relapse with CDI but there is limited data to support efficacy once the patient has had a number of relapses. In specific cases, where the patient i) is over 65 years of age, ii) has severe or fulminant illness and iii) needs concomitant antimicrobial treatment, it may be appropriate to use Fidaxomicin10,14,15. However, this treatment is comparatively expensive (£1,300 per course ex VAT) and should only be used on the advice of a consultant clinical microbiologist.

Faecal Microbiota transplant: For recurrent relapse, the most effective treatment may be a faecal transplant to replenish the patient’s intestinal flora. NICE support the use of faecal transplantation for the treatment of recurrent CDI (NICE IPG485 March 2014, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg485 )16.

Faecal transplantation has a primary cure rate of 81% with an overall cure rate of 94% (compared with Vancomycin at 31%) and donor stools are currently available through Portsmouth Hospitals.

At the point of relapse, the patient should be started on vancomycin 125mg QDS to control their symptoms and referred for faecal transplantation.

Patients can receive this treatment as a day case using a donor sample available from a donor bank which has been fully screened for safety. The procedure involves the passing of a nasojejunal tube on the day, an x-ray to check placement and the infusion of the faecal transplant via the nasojejunal tube. Although this sounds unpleasant, patients tolerate the procedure well with good clinical effect.

1. Report to the Department of Health . National Clostridium difficile Standards Group, February 2003.

2. Riggs MM, Sethi AK Zabarsky TF, et al. Asymptomatic Carriers Are a Potential Source for Transmission of Epidemic and Nonepidemic Clostridium difficile Strains among Long-Term Care Facility Residents: Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 45:992–8

3. Goldenberg JZ, Ma SS, Saxton JD, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;5:CD006095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub3.

4. Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P, et al D. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 784-90.

5. Dial S, Delaney JA, Barkun AN et al. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile associated disease. Journal of the American Medical Association 2005; 294: 2989−95.

6. Dial S, Delaney JA, Schneider V and Suissa S. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease defined by prescription for oral vancomycin therapy. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006; 175(7): 745−8.

7. Janarthanan S, Ditah I, Adler DG, Ehrinpreis MN. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1001-10.

8. Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, et al. Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 May; 57(5):2326-32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02176-12.

9. Suissa D, Delaney J, Dial S etal. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 74:2 / 370–375

10. Public Health England. Updated guidance on the management and treatment of Clostridium difficile infection, May 2013

11. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ESNM1 Clostridium difficile infection: fidaxomicin July 2012,

12. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clostridium difficile infection: risk with broad-spectrum antibiotics March 2015 NICE

13. Deshpande A, Pasupuleti P, Thota P et al. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2013: 68: 1951−61

14. Hu MY, Katchar K, Kyne L, et al. Prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1206-14.

15. Arora V, Kachroo S, Ghantoji SS et al. High Horn’s index score predicts poor outcomes in patients with Clostridium difficile infection Journal of Hospital Infection 79 (2011) 23e26

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence IPG485 Faecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. March 2014

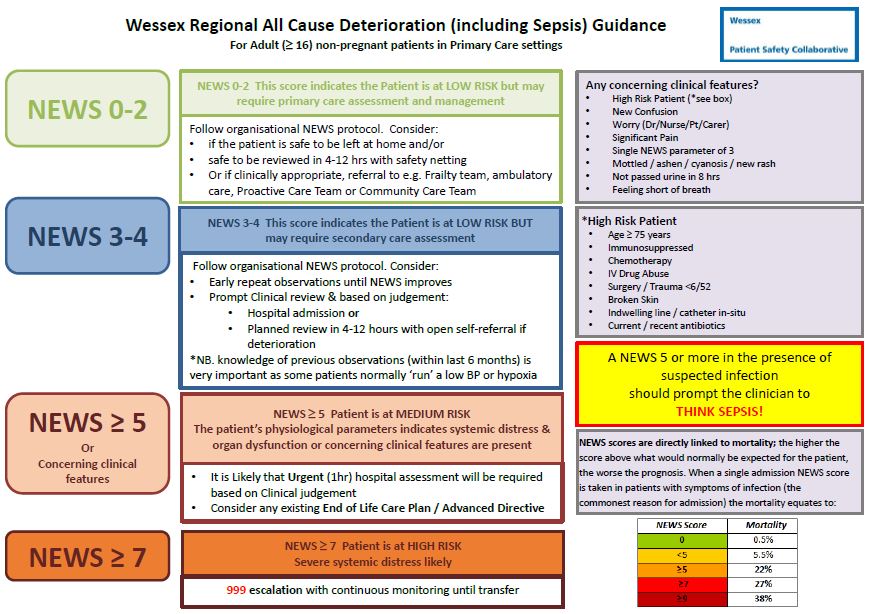

Sepsis is a time-critical medical emergency, which can occur as part of the body’s response to infection. Unless treated quickly, sepsis can progress to severe sepsis, multi-organ failure, septic shock and ultimately death. For more information and resources, please see the UK Sepsis Trust Webpages.

Sepsis affects all age groups but has a higher incidence in the elderly (95 patients per 100,000 population <65 years versus 1,220 per 100,000 >65years).1 Over 70% of cases arise in the community so general practice has an important role to play in diagnosis and rapid referral.

Sepsis is a time-critical medical emergency, which can occur as part of the body’s response to infection. Unless treated quickly, sepsis can progress to severe sepsis, multi-organ failure, septic shock and ultimately death. For more information and resources, please see the UK Sepsis Trust Webpages.

Sepsis affects all age groups but has a higher incidence in the elderly (95 patients per 100,000 population <65 years versus 1,220 per 100,000 >65years).1 Over 70% of cases arise in the community so general practice has an important role to play in diagnosis and rapid referral.

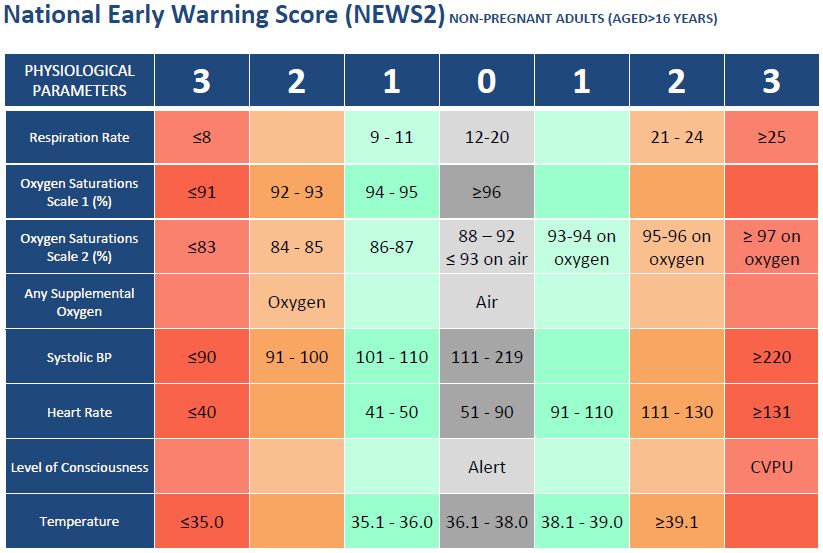

National Early Warning Scores (NEWS)

NEWS is a validated national score made up of six routinely recorded physiological parameters:

- respiratory rate,

- oxygen saturations,

- temperature,

- systolic blood pressure,

- pulse rate and

- level of consciousness

NEWS is shown to be a good predictor of mortality in the next 24 hours and improves patient survival when used by clinicians. NEWS is available on EmisWeb as a downloaded add-on.

NHS West Hampshire CCG are working with a local primary care practice to evaluate the application of NEWS to general practice and to define escalation protocols based on NEWS. We will publish more information on the progress of this project soon.

- Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, Golosinskiy A. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: A challenge for patients and hospitals.National Center for Health Statistics. 2011

- Daniels R, Nutbeam T, McNamara G et al. The sepsis six and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: a prospective observational cohort study. Em Med J 2011; 28: 507-512

- Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE et al. Duration of hypotension prior to initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1589–96

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1045–53

- Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, et al.: Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. NEJM 2010; 362: 2155-2165

- Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurology 2009; 8: 355-369

- Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre Case Mix Programme database, interrogated July 2007

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, et al. (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29: 1303–1310.

- Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 344-353

- Iwashyna TJ1, Ely EW, Smith DM,et al.Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010 Oct 27;304(16):1787-94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553.

General Practice Annual audit template

There is a statuary requirement for all providers to carry out an annual infection prevention and control audit. There is no agreed format or content for the audit, however the CCG has edited an audit created by the Infection Prevention Society (IPS) which can be used by practices if they wish. Following the completion of the annual audit, practices should create an action plan to address the areas identified as requiring improvement. Where there are risks identified, a risk assessment can be used to document the risk and actions being taken to mitigate the risk.

Annual audit: Primary Care Audit Tools 2016.xls [xls] 281KB

Action plan template: Template action plan.docx [docx] 16KB

Risk assessment template Risk assessment template for primary care.docx [docx] 133KB and example Risk assessment template for primary care – EXAMPLE.docx [docx] 27KB

Primary Care Infection Prevention and Control Policy

The Infection Control Leads (IC leads) forum members have agreed an Infection Prevention and Control Policy (General Practice -Example IC Policy[docx] 6MB) which can be used by any GP practice within the West Hampshire CCG area. The ownership and responsibility for updating the policy (every two years) is held by the IC leads. WHCCG will facilitate the regular review of the policy via the IC leads forums. IC leads are not required to use the policy within their practice.

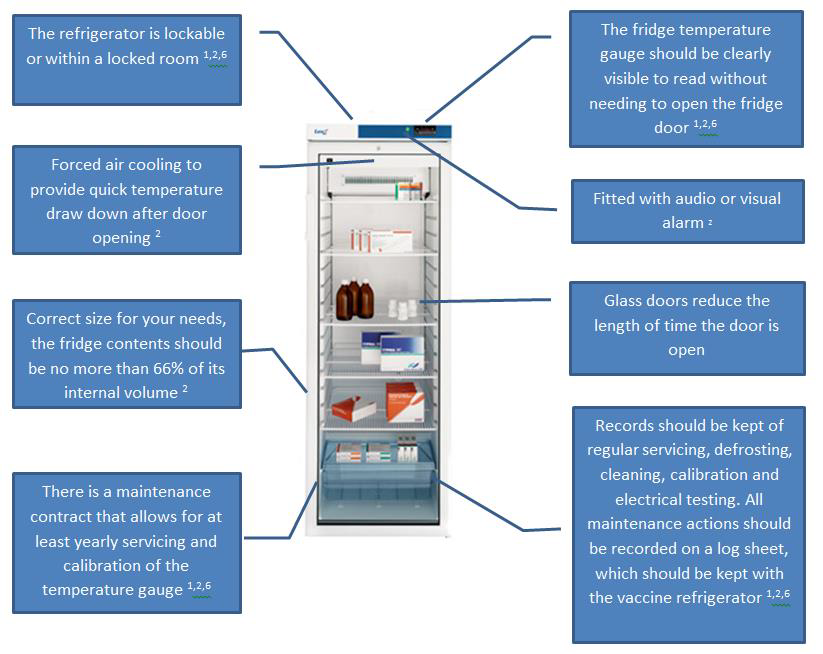

Cold Chain

Maintaining the cold chain is critical to vaccine effectiveness. Responsibility and liability for the storage and appropriate use of vaccines rests with the immunising practitioner and health service provider so it is essential that all national and manufacturers guidance is adhered to. This cold chain resource covers the following topics ( Cold Chain Information and resources pack 2016 V1.0 FINAL.pdf [pdf] 2MB ):

Cold chain management principles:

- Correct storage

- Temperature monitoring (including example recording charts)

- Transportation of vaccines outside of the practice

- Managing a chain chain breach, including using vaccines out of label

General Practice Annual audit template

There is a statuary requirement for all providers to carry out an annual infection prevention and control audit. There is no agreed format or content for the audit, however the CCG has edited an audit created by the Infection Prevention Society (IPS) which can be used by practices if they wish. Following the completion of the annual audit, practices should create an action plan to address the areas identified as requiring improvement. Where there are risks identified, a risk assessment can be used to document the risk and actions being taken to mitigate the risk.

Annual audit: Primary Care Audit Tools 2016.xls [xls] 281KB

Action plan template: Template action plan.docx [docx] 16KB

Risk assessment template Risk assessment template for primary care.docx [docx] 133KB and example Risk assessment template for primary care – EXAMPLE.docx [docx] 27KB

Primary Care Infection Prevention and Control Policy

The Infection Control Leads (IC leads) forum members have agreed an Infection Prevention and Control Policy (General Practice -Example IC Policy[docx] 6MB) which can be used by any GP practice within the West Hampshire CCG area. The ownership and responsibility for updating the policy (every two years) is held by the IC leads. WHCCG will facilitate the regular review of the policy via the IC leads forums. IC leads are not required to use the policy within their practice.

Cold Chain

Maintaining the cold chain is critical to vaccine effectiveness. Responsibility and liability for the storage and appropriate use of vaccines rests with the immunising practitioner and health service provider so it is essential that all national and manufacturers guidance is adhered to. This cold chain resource covers the following topics ( Cold Chain Information and resources pack 2016 V1.0 FINAL.pdf [pdf] 2MB ):

Cold chain management principles:

- Correct storage

- Temperature monitoring (including example recording charts)

- Transportation of vaccines outside of the practice

- Managing a chain chain breach, including using vaccines out of label

Water Safety (Legionnaires’ Disease) in Primary Care

Primary Care practices have a duty to ensure that their water systems do not pose a risk to the health and safety of employees and visitors (e.g. patients, hosted staff and contractors) from Legionella bacteria under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations (COSHH) and the Health & Safety at Work Act.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) also expects practices to fulfill these obligations to demonstrate compliance with the essential standards of quality and safety (Outcome 8: cleanliness and infection control and Outcome 10: safety and suitability of premises).

All water systems in Primary Care practices require a risk assessment. However not all systems will require elaborate control measures and responses and actions should be proportionate to the identified risk. A simple risk assessment may show that the risks are low and being properly managed to comply with the law. It is likely to that most practices will not require anything more than a basic local risk assessment and simple in-house control measures.

This document ( Water Safety Pseudomonas and Legionella v3.pdf [pdf] 405KB ) is a summary designed to introduce Primary Care practices to the requirements around water safety and help practices determine whether external consultation is proportionate and necessary. Please also use this link to the Wessex LMC.

Clinical Best Practice Guidelines

- Surgical Site Skin Preparation – Current Evidence and Recommendations

There is currently a lack of good quality, controlled studies comparing skin preparation regimes for surgical procedures and surgical site infection outcomes.

Many different commercial solutions are available and clinicians may be unsure what is the best disinfectant preparation to use. This document ( Skin Prep Best Practice Guidance (final version).pdf [pdf] 360KB ) compiles the latest NICE recommendations and summarises the best existing evidence to allow clinicians performing minor surgery procedures in primary care to make an informed choice over skin preparation based on the available knowledge to date.

- Best Practice Guidelines for Phlebotomy (Infection Prevention and Control)

The CCG has put together a two page summary ( Best Practice in Phlebotomy Practice Guidelines.pdf [pdf] 248KB ) of the infection control guidance provided in the WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION guidelines on drawing blood: best practices in phlebotomy 2010.

These are best practice guidelines, rather than national standards. However, practices should be achieving or working towards the best practice recommendations to protect patients and staff, or have a risk assessment in place where the guidance cannot be adhered to.

For practices or federations undertaking phlebotomy, two audit tools (for premises and practice) are also available here: Phlebotomy Audit Tool.docx [docx] 138KB.

Posters for generic use

NPSA colour-coding for cleaning materials National colour coding scheme.pdf [pdf] 308KB

Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) CDC ppe-poster.pdf [pdf] 2MB

Segregation of healthcare waste Segregation of Healthcare Waste Poster Colour.pdf [pdf] 356KB

Splash and Sharps Injury Sharps Safe EU Directive.pdf [pdf] 131KB

Cover your Cough Cover your Cough Poster.pdf [pdf] 363KB

Hand gel Hand Gel Poster.pdf [pdf] 254KB

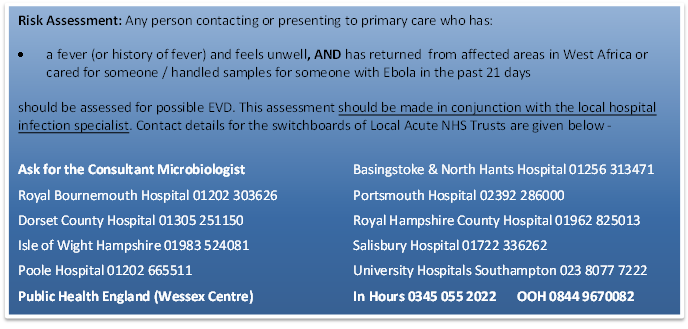

Viral Haemorrhagic Fever – Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)

Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers (VHF) imported into the United Kingdom (UK) are an extremely rare event and there have been no cases of person-to-person transmission in the UK to date. Even with the current Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, it remains unlikely, although not impossible, that Primary Care services will see imported cases.

Current Public Health England (PHE) guidance prepared in conjunction with the GPC of the British Medical Association around managing patients who require assessment for EVD in primary care is available here:

Supplementary Guidance: Preparing for Ebola Virus Disease in Primary Care Supplementary Guidance Preparing for Ebloa in Primary Care WP.pdf [pdf] 320KB

Supplementary Guidance: Actions for Practices Supplementary Guidance Action for Practices.pdf [pdf] 189KB

Supplementary Guidance: Practical Patient Management Supplementary Guidance Practical Patient Management.pdf [pdf] 300KB

Supplementary Guidance: Staff Protection Supplementary Guidance Staff Protection.pdf [pdf] 360KB

Supplementary Guidance: Cleaning and Decontamination Supplementary Guidance Cleaning and Decontamination.pdf [pdf] 208KB

Supplementary Guidance: What is happening when people enter the UK from an affected country? Supplementary Guidance Screening people from an affected country.pdf [pdf] 291KB

Key Messages:

Ebola virus is only spread through symptomatic individuals. Asymptomatic contacts of Ebola virus cases do not pose an immediate public health risk

Person-to-person transmission of Ebola virus is by direct contact with blood or body fluids of a symptomatic person (e.g. saliva, vomitus, urine, stool, semen) or indirect contact with contaminated clothing / equipment

There is no evidence of transmission of Ebola virus through intact skin (i.e. social contact) or small droplet spread such as coughing or sneezing

The onset of illness is sudden, with fever, headache, joint and muscle pain, sore throat and intense weakness. The risk of a symptomatic patient presenting to Primary Care with the additional progressive symptoms of diarrhoea, vomiting, rash and internal and external bleeding is extremely low

West Hampshire CCG supports quality in primary care and welcomes the opportunity to work with practices to support their infection prevention agenda.

The CCG has a dedicated Infection Prevention Nurse Specialist that practices can access for advice.

Help preparing for Care Quality Commission (CQC) visits

The CCG has been offering local practices the opportunity to participate in preparatory CQC style Outcome 8 inspections. The purpose of these visits is to identify areas of good practice and to provide specialist advice where practices may need help in complying with the Code of Practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance (2008). The advice is based on the best available evidence and aims to be proportional to the risks associated with primary care and the types of interventions being performed. The infection prevention service is very much a voluntary partnership between the CCG and primary care. All visits are initiated on the request of the practice concerned.

If you are a healthcare professional and your practice is interested in a supportive visit, please contact Matthew Richardson. If you are a patient and would like further information, please contact us by clicking here.

The Role of the Infection Prevention & Control Lead (Primary Care)

The Code of Practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance (2008) requires every Primary Care provider to have an Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Lead.

The IPC Lead is responsible for the local infection prevention and control programme. Briefly, this involves identifying the risks to the practice, its patients and staff from infection, and taking responsibility for implementing and monitoring actions to manage those risks. Further details on the role and suggestions for responsibilities to be included in their job descriptions can be found here: The Role of the Infection Prevention and Control Lead.

Completing the Annual Statement for Infection Prevention and Control (Primary Care)

It is a requirement of The Health and Social Care Act 2008 Code of Practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance that the Infection Prevention and Control Lead produces an annual statement with regard to compliance with good practice on infection prevention and control and makes it available for anyone who wishes to see it, including patients and regulatory authorities. A template to help practices can be found here: Infection Prevention and Control Annual Statement

Induction and On-going Education for Primary Care workers

The Code of practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance (revised July 2015) requires appropriate induction and on-going education for all Primary Care workers to protect staff and patients. Further details on education requirements with a suggested training matrix can be found here: IPC Education Requirements August 2015.pdf [pdf] 320KB